Hip-hop has classics. There’s no disputing that. But genres like jazz and the blues acknowledge “standards”—songs that get covered and reinterpreted as the music evolves. Hip-hop has not established a standard canon per se. However, it sometimes comes close, like with Ice Cube’s “Check Yo Self” remix and Puff Daddy’s “Can’t Nobody Hold Me Down.” Both sample Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five’s “The Message,” with each artist continuing to address the tribulations of Black Americans from the imprisoned to the affluent. Amsterdam-by-way-of-Israel producer Soul Supreme (birth name Noam Ofir) did not intend to introduce a standard canon, but he’s found a lane in creating jazz versions of hip-hop classics on his Fender Rhodes and Moog Subsequent 37, including an interpolation of “The Message.”

“Hip-hop is the perfect art form for it,” Soul Supreme says. “You can take a song from the ’90s that samples one song from the ’80s, another drum break from the ’60s, and a remake of a song from the ’40s. It’s all on the same song. You can really navigate between these worlds. And add how the MCs and DJs were shifting it in their own ears. You have all that as a palette to choose from.”

His knowledge stems from decades dedicated to the art form, a process he describes as organic while growing up in Israel. He began with b-boying and graffiti, until back pains led him to DJing and purchasing his first MPC. Success from DJing inspired a move to Europe to pursue it professionally but led to day jobs and feeling an inkling to return to the piano lessons he’d never been much good at as a teenager.

“I was introduced to Buscrates and Tall Black Guy, people who were really introducing keys into their production, not just samples,” he said. “I felt like it was the next step. I started experimenting.”

Soul Supreme’s ability to see a full history becomes increasingly defined through his dedications to A Tribe Called Quest, Madlib, and J Dilla. On the recently released “Award Tour (We Gettin’ Down)” b/w “Bonita Applebum (Daylight)” 45, he deliberately cites the A Tribe Called Quest titles alongside the sampled titles from artists Weldon Irvine and RAMP. The instrumental production is stripped of its verbatim interpreting for a more nuanced voyage between ’70s soul and jazz. On the “Bonita” cover, the layered horns create a big-band take on the psychedelic Rotary Connection sample before kicking in the low-end thump of a Q-Tip classic. Whereas Soul Supreme’s version of Cortex’s “Huit Octobre 1971” leans on the jazz-funk movements, oscillating between deep grooves and cosmic keys, rather than the Madlib loops that became MF Doom’s “One Beer.”

“I started making versions of the song, just deconstructing them to understand them better,” Soul Supreme says. “I wasn’t inspired by other people doing it. One exception would be Miguel Atwood-Ferguson. His Dilla project [Timeless: Suite for Ma Dukes] showed me you can do something really amazing with these versions. Just take something to a completely new place.”

The versions were not originally written to be released. It was an incidental discovery from posting a video of his “Umi Says” cover on Instagram. Followers clamored that he should put the Mos Def cover out on wax. Tim Zawada of Star Creature Universal Vibrations took notice and offered to release “Umi Says” and “The Message” in 2019. The success of the 45 encouraged Soul Supreme to keep exploring versions, and in 2020, he founded his own imprint. It was a move that was encouraged by DJ Kon, who said, “Why do you expect other people to invest in your music if you’re not willing to bet on your own?” But when it came to launching the imprint with pressings in a pandemic, many confidants suggested he delay the releases.

“Trust your gut,” Soul Supreme says. “I did it exactly at the beginning of the pandemic, and everyone I asked told me not to do it because these are really bad times to release music. My gut was telling me the other way around. People are sitting at home all day. They have nothing to do.”

Soul Supreme’s philosophy with art is that an artist has to “risk their rent” when it comes to investing in themselves. “If you believe in your music, you have to do it,” he says. He recognizes it might not be universally applicable, but it has worked for him. His small-batch 45s sell out within hours.

But Soul Supreme has not stuck to the covers lane. Within that first year of the imprint, he released his self-titled debut, which was partially recorded in Vienna, Austria, while he produced a friend’s reggae band. He took the gig with the caveat that on the last day, the band, largely composed of jazz musicians, would record for him. They had one hour.

“Every night, they’d finish recording at 10:00 or 11:00 in the evening, and I’d stay awake until three just working on ideas for the last session,” he said.

The result is an exploratory jazz-funk record that thumps and moves with both hip-hop and house influences, live instrumentation, and electronic synthesis. While the debut does include two dedications, the Cortex cover and Tony Palkovic’s “Born With a Desire,” the core of the album glistens from Soul Supreme’s compositions. He said he feels that influences should shine through and that the moment an artist is pursuing a genre sound, there’s a melodic lock on the music.

“I don’t find that a version is less original than a so-called original,” he says. “With a version, if you do it in an imaginative way, you can reach really creative ideas that in a so-called original would not necessarily be there. Many times, people think that if they sound like other people, there’s a better chance of them making it as an artist, which is kind of missing the point. [Thelonious] Monk said the greatest thing is to sound like yourself. That takes a lifetime for most, if any.”

From his record collection, Soul Supreme selected “a mix of records I’ve been listening to in the past two years and also records that have affected my sound.”

RECORD RUNDOWN

Johnny Hammond Gears (Milestone) 1975

First of all, a good record. The writing, the arrangements—it’s the top of the Mizell Brothers era. Their productions were rich in the sense of how much the layers and different ideas align. It’s still cohesive. It doesn’t sound like it’s trying to be complex. It’s just using a lot of different tools to give a certain emotion. It’s such a beautiful era in musical history. The level of playing is insane. The level of arrangements are insane. And the mixing and recording are really insane. It’s the best of all worlds for me.

It sounds like it’s more Mizell than [Johnny Hammond], but that’s not necessarily a bad thing. The combination of traditional instruments with new electronic instruments. A lot of people did it, but they did it in their own special way. I don’t do it like them, but I do incorporate mixes of different layers of synthesizers and electronic stuff and live instrumentation. I like that combination.

People Under the Stairs O.S.T. (OM Records) 2002

I don’t remember who, but somebody basically said, and this might have been right after Double K died [in 2021], when you had this beautiful wave of underground hip-hop in the late ’90s and early 2000s, while you had Madlib, Doom, and Quas doing all kinds of esoteric stuff, these were legends but not people you actually knew. People Under the Stairs were like your friends, kind of, even though you don’t know them. They are more like everyday people who make amazing music. Even though I was growing up in Jerusalem, half a world away, it was just something I could connect to.

Thes One and Double K were really honest about who they are. That’s something, for me, that I consider one of the most important things in music. It translates directly with being yourself, [which] is the greatest achievement of an artist. For me, Thes One and Double K were that.

Don Blackman Don Blackman (Arista) 1982

It’s one of those records where the writing, the arrangements, the playing especially, the mixing, you could not make it any better. I wish Don Blackman would release more albums. The world could use more of his music. The ’80s were already starting to get into electronic boogie-funk, and he’s a jazz pianist and a super soulful person, so everything is just coming together at the right time. The bass lines are so on point.

John Coltrane Coltrane’s Sound (Atlantic) 1964 [recorded October 24, 1960]

Coltrane obviously has a lot of amazing albums. It’s difficult to choose one. The energy is crazy. Coltrane in this period was very melodic. It’s before McCoy got really into quartal harmony. He’s super soulful on it. The arrangements, man. That’s something I really take a lot of inspiration from. They take standards that are way older, but make it sound completely modern for the time just by changing everything. I try to push the same kind of approach with my versions. Take some stuff from the original but also present it in a different way. Not to try to compare myself ever with any of these giants, but I do take inspiration from how they approach older material and really revive it.

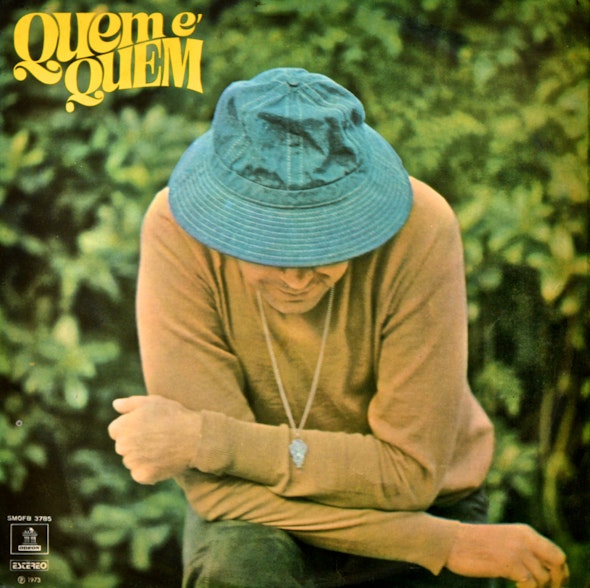

João Donato Quem É Quem (Odeon) 1973

It’s one of my all-time favorite Brazilian records. It’s incredibly cohesive and he has such a unique sound. Of course, the Rhodes controls that album. It’s a sound I love and an era I love. It’s simple, yet complex.

When did you first hear João’s music?

It was probably high school, and I’m not sure how. That was a time of exploration. There were a lot of blogs by people who liked music and shared it. João before that has a piano period; he has a few samba and Brazilian jazz albums that I completely love. But Quem É Quem, for me, the compositions, the arrangements, and sound, it’s my favorite piece of work he’s done. I know how to play the songs. They just make me feel good when I hear them. I try to take from everything, but it’s not like I studied him specifically. I just love the way he sounds.

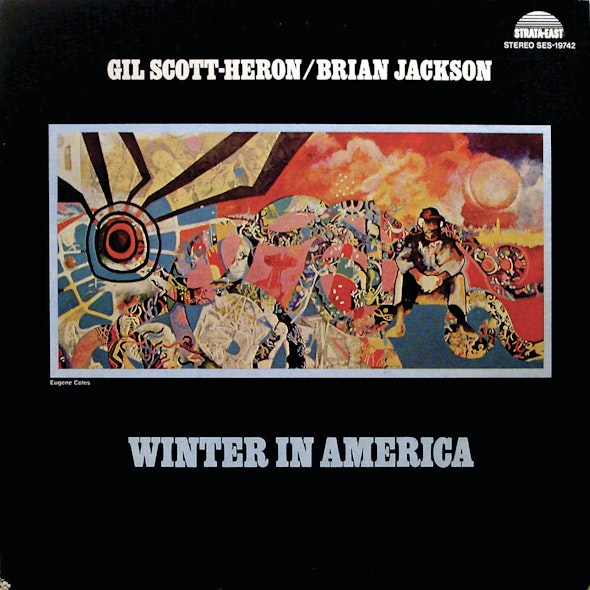

Gil Scott-Heron and Brian Jackson Winter in America (Strata-East) 1974

Lyrically, musically, it’s just such a standout album. Honesty. You can hear honesty. To tap into Coltrane a bit, there’s the human experience. And it’s genuine. I might not have gone through the same things, but I can have empathy and perceive something as being honest and touching. When I listen to it, it’s just the truth. It’s a real emotion. Brian Jackson was the perfect musical partner for him. His playing is really honest. There’s no showboating. He’s essential to make you feel how the lyrics feel.

Organized Konfusion STRESS: the Extinction Agenda (Hollywood BASIC) 1994

There’s a lot of melodicism in the way Prince Po and Pharoahe Monch rap. It’s an emotional album. The way the music matches the lyrics and the emotion. For me, it’s an outlier. Everything is perfectly serving the emotion of the music. I probably own all the samples on the album and I’ve tried to look for all the breaks. It’s a combination of their own production, but also Buckwild, who is someone from my hip-hop nerd days on the MPC, and still someone I probably like the most. It’s difficult to pinpoint, but the music serves the emotion.

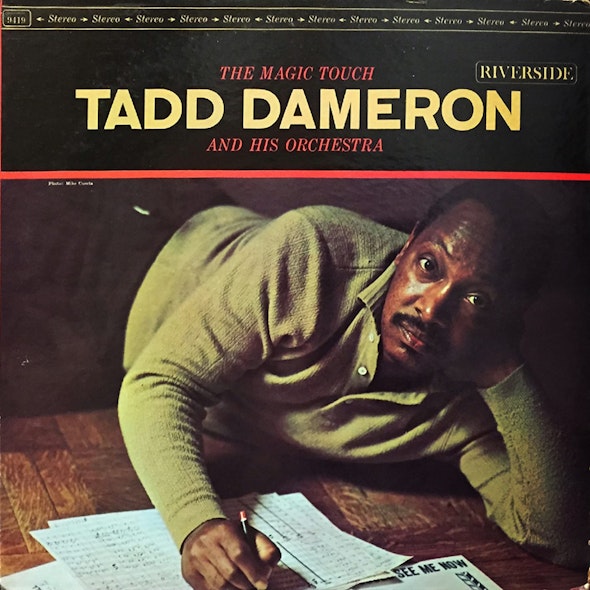

Tadd Dameron and His Orchestra The Magic Touch (Riverside Records) 1962

I’m not sure most Wax Poetics readers will like this one. Tadd Dameron, for me, is one of the greatest composers of the bebop era. This is the only one he did for himself where it’s a big-band session for his music. It’s super rich with ideas. He has his own language. When [pianist] Bill Evans plays with certain rhythm sections that are more soulful and the bebop type of thing, he plays more bluesy. This session, he definitely plays this way. It’s very different from his usual playing.

The Pharcyde Labcabincalifornia (Delicious Vinyl/Capitol) 1995

I should probably choose a Tribe [Called Quest] record, but I love the Pharcyde’s Labcabincalifornia as much. Both of Pharcyde’s albums are fucking amazing. I do think it taps into the world of Freestyle Fellowship and Hieroglyphics as well, of connecting hip-hop more to jazz and much more creative freedom when it comes to West Coast hip-hop. I don’t know if it was a counter movement, because I’ve never read about this, but it feels like coming from NWA and Death Row, this is completely the opposite side.

Labcabin is a bit more mature musically [than their debut, Bizarre Ride II the Pharcyde]. But the Jay Dee stuff is just fucking amazing. This Jay Dee era is probably the one that influenced me the most. The “She Said (Remix)” is even better than the original, and they are both produced by Jay Dee. Or maybe it’s not better. I couldn’t pick between the two.