Prince Rogers Nelson was a miniscule Minnesotan who seemed to float down from the heavens one day in the early ’80s fully formed. The velveteen virtuoso constructed stylized narratives and fictionalized versions of his childhood, artistic origins and personal and business experiences as his star began to rise—He had his stories and he stuck to them. Prince’s self-mythologizing skills were as tight as the snug velvet stage slacks he wore for performance and impromptu sports showdowns. He possessed a deep-rooted, intrinsic motivation to catalyze innovative collaborations and futuristic music arrangements that won him zillions of breathless fans, worldwide fame, and great commercial and fiduciary success.

As he morphed into a worldwide musical and cultural phenomenon, his dark side started to reveal itself to those following along with music industry soap-opera plot points within his world. The Paisley Park camp really took dramatic band fights and theatrical exits from the group to a performance-art level. That’s why the tale lent itself so easily to Prince’s cinematic offerings. One could hypothesize that the Lilliputian one overcompensated for insecurities as he fought for adulation as a solo artist and to be taken seriously as a genius across the arts. He got more eccentric as his glittery lavender star began to rise, despite having a huge stable of talented musicians, studio wizards, and behind-the-scenes pros on his team supporting him, and began to set absurdly strict and suffocating rules for his own band, exacting punishment on those who didn’t fall in line with the new power generation regime.

The public’s first glimpse of Prince-as-Svengali was when he put together his first supergroup, the Time (some have speculated that he was inspired by the 1980 film The Idolmaker, in which a string-pulling manager calculatingly creates a superstar). He spun that band’s story to cast himself as a savior who plucked a gaggle of shabby lost-soul Midwestern musicians out of obscurity, while the truth is that he found all of the members of the Time while they were working in their own popular local bands. Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis, who went on to become two of the most successful American R&B music producers, had an outfit called Flyte Time that was decimated as Prince was curating and casting the Time. Prince convinced Jam, Lewis, and their singer Alexander O’Neal to leave and join his power funk brigade (O’Neal was quickly fired in the first of many scandalous personnel switcheroos). Morris Day and Jesse Johnson were poached from the group Enterprise of Pleasure. The stories of unrest within the band are legendary, and the group splintered in many different directions as they all got fed up with being subjugated subjects of the purple kingdom.

With zealous Prince fans teeming in the record-buying community, it’s both practical and fascinating to veer into Prince-adjacent territory to discover other off-the-radar albums culturally significant in the context of Prince Rogers Nelson. There are many paths that lead to the signature Minneapolis sound of synthesized swing that melds elements of rebellious funk; digital, angular new wave; and modern soul sensibility. The flotsam and jetsam that Prince left behind as he went barrelling through time is just as engaging as the iconic albums that emerged from Prince and his Jamie Star productions.

Some may not recognize the name Jesse Johnson immediately when looking at the lineup of the Time, but his name rings out in the classic Time cut “Jungle Love” as the boisterous shouts of “Hey Jesse! Now Jerome! Check it out!” punctuate the anthemic number featured prominently in Purple Rain. After Jam, Lewis, and O’Neal departed the Time, the rest of the group dissolved in reaction to Prince’s increased megalomania and Draconian rules. Three members formed the Family, but guitarist and singer Jesse Johnson took the solo route, releasing three albums of his own. If we jump another layer away from Prince, we find a winner of an album produced by Johnson as he took on studio roles.

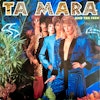

Johnson apparently wrote but did not receive credit or royalties for breakout hit “Jungle Love.” And he never let go of the jungle theme. Case in point is Ta Mara and the Seen, a divine group put together by Johnson in 1985. Animal prints abound on the cover of this lesser-known Minneapolis LP—the font mixes several patterns of it, and two of the five members are wearing kimono blazers created out of animal fabric. The opening of the first track features tribal drum beats and squawking bird calls by way of introducing a stomper of an ’80s dance-floor filler, “Everybody Dance.” Some songs on this album come close to making the jump to feverish New York–style freestyle with their relentless computerized rhythms tailor-made for doing the wop or bumping and grinding in an era-appropriate way.

I enjoy reading too much into song titles, and it’s not a hard leap to guess that many of these tracks nod to Johnson’s shadowy history with Prince. “Long Cold Nights” could be literally and figuratively about the struggles of the Minneapolis musician thwarted by Mr. Rogers Nelson. The true burner on this album—it’s worth seeking out the 12-inch remix of it in addition to the LP version—is the sleazy but gorgeous song of longing “Affecttion” [sic]. Prince spent his entire time on Earth tirelessly trying to fill his life with huge, artistically fulfilling musical and film endeavors. He sought to be surrounded by an obsequious entourage, adoring lackeys, beautiful lovers, and the most skilled musicians possible who were only present to serve his broader goals as he worked, yet Prince still seemed to be alone in his ornate compound at the end of his life, still hoping to find that affirmation he needed to feel whole and to slow down. Instead, he worked maniacally on myriad undertakings and dropped and added people to his personal roster frequently. He didn’t ever seem to lean back and say, “Ahh yes, now my soul is satisfied.” The simple lyrics of “Affecttion” could be about the yearning for a one-night or long-term lover, but they could also be the story of regret and wishes for things to turn out differently for Prince and his protégés. They all desired to connect, collaborate, and make music together that would put Minneapolis’s innovative sound on the world’s radar. They just couldn’t meet in the middle.

I like to think the extra T in “Affecttion” stands for “time,” both the supergroup and the precious amount of it lost as these Midwestern men jockeyed for position in the music scene and larger business. Prince, Johnson, Day, Lewis, and Jam all had the same goals coming up—they wanted to make cutting-edge music that resonated throughout the world. They all had to play on, despite the intense ups and downs of their careers, both together and individually. That’s what they were all meant to do. Luckily for listeners, there is a huge catalog of records that document the drama that played out in the Twin Cities and beyond.

In the end, who really created the Minneapolis sound? Were Jesse Johnson and his cohorts integral to the architecture of that specific style of music or were they merely continuing what originated with the short man enrobed in purple? Ultimately, the question is moot. Jump off from any member of the Time in any direction and excellent offerings are there for the taking, waiting to be heard and bopped to.