Somewhere in Lower Manhattan, in the late ’70s, a fever dream was taking hold. Commerce, drugs, and art were clawing their way out of the primordial cesspool that had taken over New York City; while four hundred years earlier, in the Kingdom of Bhutan, the Drukpa (or Dragon People) flapped their wings and changed the weather for two sons of Steel City.

Back to the mid-’70s, Walter Steding’s Tesla coils sparked the imagination of pop impresario Andy Warhol. Walter had hopped the avant-garde art express from Pittsburgh to NYC. As a teen, Steding had been taken with the likes of Stockhausen and taught himself to play the violin as a medium through which he could produce sounds on his jerry-rigged electronic boxes. Once in NYC, he quickly fell in with Warhol and the Factory crowd who were wowed by his electrified violin performances. Walter remembers his leap at the birth of the downtown no-wave scene from one-man band opening for Blondie at CBGB to full-fledged rock outfit: “I was playing at the Mudd Club with my blinking eyeglasses and my synthesizer belt all connected to my head. It was a lot of screaming and loud sounds, but I kind of knew enough to keep it quick. Once I made my statement, I wasn’t demanding that rock and rollers in a nightclub listen to some avant-garde music concert. [Drummer] Lenny [Ferrari] was in the audience, and he said, ‘Walter, don’t you realize there are people forming small groups here to decide who’s going to beat you up first?’ And then he said, ‘But, you know, this is the kind of band I want to be in!’ So he added a dynamic, powerful beat behind what I was doing.”

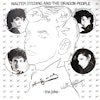

The Dragon People came together with the addition of Ruby St. Catherine on bass, Karen Geniece on guitar, and Claudia Summers on Oberheim synthesizer. Warhol wanted to be Walter’s manager, and they started Earhole Productions together. “When I asked [Andy] what music he liked to listen to on the radio,” Walter recalls, “he just said, ‘The news.’ So he didn’t really have that much input. Of course, he understood it and appreciated it culturally.”

Walter wanted to take advantage of the medium of rock and roll, and with Blondie’s Chris Stein lending a punky sheen as producer, he was heading in the right direction. Although he already knew the punch line to the joke was himself—he never had imagined fronting a traditional-style rock band—he didn’t want to be totally antagonistic. “I tried to incorporate that art [form] to the character that I was portraying and stick to the format that was already established.”

Originally published in Wax Poetics Issue 45, 2011.